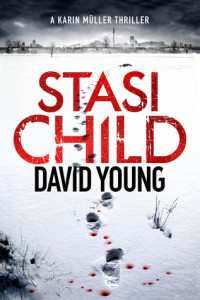

When Oberleutnant Karin Müller is called to investigate a teenage girl’s body at the foot of the wall, she imagines she’s seen it all before. But when she arrives she realises this is a death like no other: the girl was trying to escape – but from the West.

Müller is a member of the national police, but the case has Stasi written all over it. Karin is tasked with uncovering the identity of the girl, but her Stasi handlers assure her that the perpetrators are from the West - and strongly discourage her asking questions.

The evidence doesn’t add up, and Muller soon realises the crime scene has been staged. But this is not a regime that tolerates a curious mind, and Muller doesn’t realise that the trail she’s following will lead her dangerously close to home . . .

Today I am VERY happy to welcome David to the blog as part of the official tour – Stasi Child really is the most amazing read and I’ll be doing a full review very soon – in the meantime here David tells us about early writing and reading. Over to David.

Early Writing and Reading.

I think it’s a truism that most newly-published authors have been desperate to break into print for a long time, writing stories in one form or another for most of their lives. For me, that’s only partially true. At the start of the noughties I wrote two crime thrillers set on the Isle of Wight that I couldn’t find a publisher for, and then turned to another diversion from the day job – in my case songwriting – until the urge to write a novel struck again about three years ago.

But if I delve back many, many years to early childhood perhaps there’s a clue what was in store. I clearly remember, aged about five, writing and illustrating my own version of the story Black Beauty when I was round at a neighbour’s one afternoon. I was very excited about this and fully expected to get it published. My mother let me down very gently, explaining that Black Beauty had already been written by Anna Sewell, and that there wouldn’t really be a market for a version by David Young, never mind any copyright issues. I think this provoked a few tears and a strop but eventually I had to accept it.

Although this setback thwarted a very early writing career, it didn’t stop me reading. My favourite reading material was the now often-maligned Enid Blyton. I was addicted to Blyton’s ‘Mystery’ series (interestingly, The Mystery That Never Was, is one of her controversial titles, rejected by her usual publisher, Macmillan, because: “There is a faint but unattractive touch of old-fashioned xenophobia in the author’s attitude to the thieves; they are ‘foreign’ … and this seems to be regarded as sufficient to explain their criminality”).

Blyton wrote them prolifically and I read them prolifically, and that was my first introduction to what was – I suppose – a form of crime fiction for children. I think it was from reading a technique in a ‘Mystery of’ book that I acted out my very own locked room ‘mystery’. This involved my sister locking me in the toilet with nothing but a sheet of newspaper. I then slid this under the door, carefully knocked at the lock till the key fell out onto the paper, and then slid the key – on the sheet of paper – back inside the toilet and then – hey presto! – unlocked the door from the inside. There is one scene in Stasi Child involving a scam to get photographs of tyre imprints from government cars which was probably inspired by something similar in a Blyton book.

Much against my wishes, I was packed off to boarding school at the unfeasibly young age of nine for no better reason – it seemed to me – than for my parents to be able to boast about it to their friends. I still read books to fight off loneliness and boredom, but any formal English Literature aspirations were rather thwarted when the school entered our top set into an advanced English Lit ‘O’ level a year early. The main reason it appeared to me was so the English master could get a vicarious thrill from quoting from Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale to a roomful of 15-year-old boys. His favourite passage was when character ‘x’ grabbed character ‘y’ (I can’t remember who) ‘by the quaint’ – an old-English term for the unmentionable ‘c’-word. I didn’t thrive in this environment, and instead opted to do science ‘A’-levels.

But I guess the biggest influence on Stasi Child from my childhood years came from thriller writers Helen MacInnes and Alastair MacLean. Both are less well-known these days, although MacLean’s name is perhaps more familiar because of the success of films like The Guns of Navarone and Where Eagles Dare, which still get regular reruns on some of the minor TV channels. In her day though, Scottish scribe

MacInnes was the Queen of thriller writers, and I was an addict in my teenage years, buying each new title as soon as it came out. She took the reader on thrill-a-minute tours of Europe in titles such as The Salzburg Connection (1968). I hope some of that excitement has spilled over into Stasi Child. Its perhaps most noticeably evident in a scene on The Brocken – which was the highest mountain in the northern part of East Germany, site of the main listening station trying to intercept messages from the West. My heroine – Oberleutnant Karin Müller – is involved in a helter skelter ski-chase, followed by a shoot-out – something that could have come straight from a MacLean or MacInnes novel. What I loved about each of those two author’s tales was that you were almost guaranteed a damn good read. So if people say the same of Stasi Child, I’ll consider it’s been a success.

You can follow David on Twitter here https://twitter.com/djy_writer

Buy the book: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Stasi-Child-Oberleutnant-Muller-Series/dp/1785770063/ref=tmm_pap_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1445320831&sr=1-1

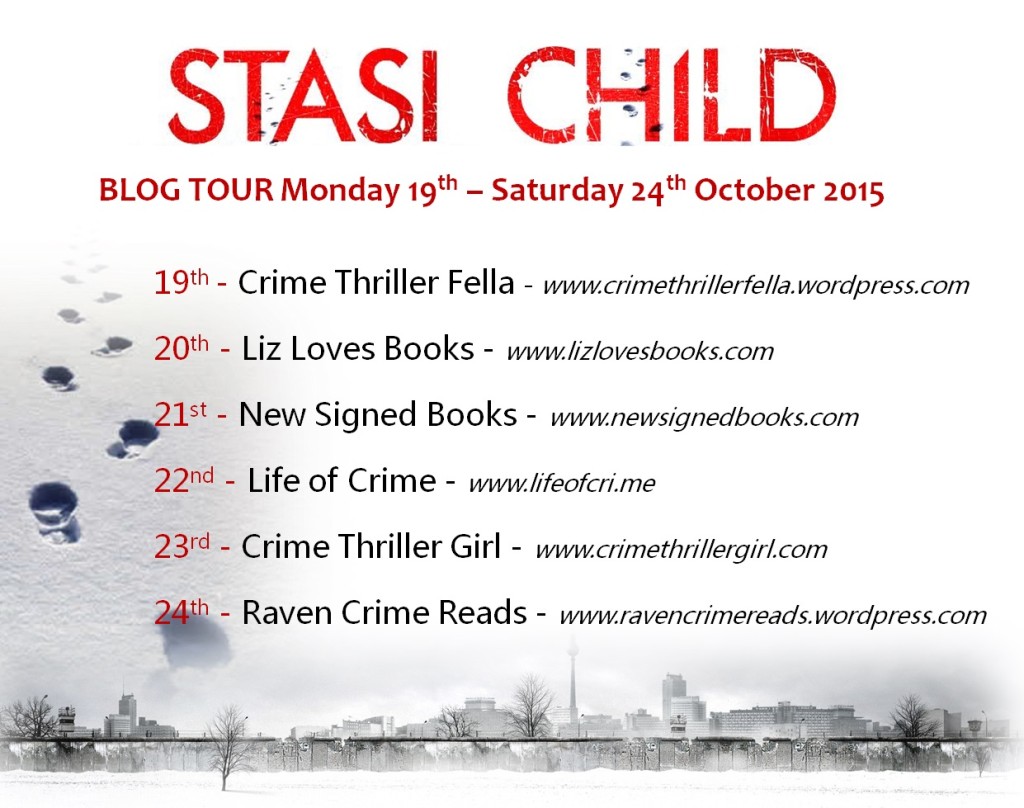

Find out much more: Follow the tour.

Happy Reading Folks!