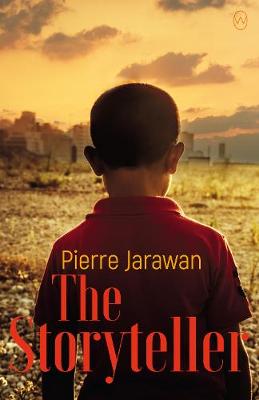

The enthralling search for a missing father

Samir leaves the safety and comfort of his family’s adopted home in Germany for volatile Beirut in an attempt to find his missing father. His only clues are an old photo and the bedtime stories his father used to tell him. The Storyteller followsSamir’s search for Brahim, the father whose heart was always yearning for his homeland, Lebanon. In this moving and gripping novel about family secrets, love, and friendship, Pierre Jarawan does for Lebanon what Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner did for Afghanistan. He pulls away the curtain of grim facts and figures to reveal the intimate story of an exiled family torn apart by civil war and guilt. In this rich and skillful account, Jarawan proves that he too is a masterful storyteller.

The Storyteller by Pierre Jarawan

Translated from the German

by Sinéad Crowe and Rachel McNicholl

1992.

Father was standing on the roof—balancing, rather. I was standing below, shielding my eyes with one hand and squinting up at him, silhouetted like a tightrope walker against the summer sky. My sister sat on the grass, waving a dandelion head and watching the tiny seed parachutes twirl. Her legs were bent at the kind of unnatural angles only little children can achieve.

“Just another little bit,” our father shouted down cheerfully as he was adjusting the satellite dish, his legs spread wide to retain his balance. “How about now?”

On the first floor, Hakim stuck his head out the window and shouted: “No, now there’s Koreans on the tv.”

“Koreans?”

“Yeah, and ping-pong.”

“Ping-pong. How about the commentary? Is that Korean too?”

“No. Russian. Koreans playing ping-pong, and a Russian commentator.”

“We don’t want ping-pong, do we?”

“You might be too far to the right.”

By now my head was also caught up in a game of pingpong, looking back and forth to follow their conversation. Father pulled a spanner out of his pocket and loosened the nuts on the mounting. Then he produced a compass and skewed the satellite dish a bit more to the left.

“Don’t forget—26 degrees east,” shouted Hakim, before his grey head vanished back into the living room.

Before going up on the roof, Father had given me a detailed explanation. We had been standing on the small strip of grass in front of our building. The ladder was already up against the wall. Sunlight shimmered through the crown of the cherry tree and cast magical shadows on the pavement.

“Space is full of satellites,” he said, “ten thousand of them and more, orbiting the earth. They tell us what the weather will be like, they survey earth as well as other stars and planets, and they relay tv to us. Most of them offer pretty awful tv, but some of them have good programmes. We want the satellite with the best tv, which is just about there.” He looked at the compass in his hand and kept rotating it until the needle lined up with the 26-degree mark on the right-hand side. He pointed at the sky, and my eyes followed his finger.

“Is it always there?”

“Always,” he said, and bent down, stroking my sister’s head before picking up two cherries that lay in the grass. He put one of them in his mouth. He held the other out at our eye level, and, holding the stone of the eaten cherry in the fingertips of his other hand, revolved the stone around the whole cherry. “It travels around the earth at the same speed as the earth spins on its axis.” He drew a slow semicircle in the sky with the stone. “That’s why it’s always in the same position”.

The idea of extra-terrestrial tv appealed to me. I was even more taken with the idea that somewhere up there a satellite was in orbit, always in the same position, always following the same course, constant and reliable. Especially now that we too had found our fixed position here.

“Is that it now?” Father shouted again from the roof.

I shifted my gaze to the living-room window, where Hakim’s head appeared instantly.

“Not exactly.”

“Ping-pong?”

“Ice hockey,” shouted Hakim, “Italian commentator. You must be too far to the left.”

“I must be mad,” answered Father.

In the meantime several men had gathered on the street in front of our building, offering pistachios around. On the balconies opposite, women had stopped hanging out their washing and were watching the action with amusement, their hands on their hips.

“Arabsat?” shouted up one of the men.

“Yes.”

“Great tv,” shouted another.

“I know,” replied Father, as he loosened the nuts again and adjusted the dish a bit to the right.

“Twenty-six degrees east,” called up one of the men.

“Too far to the left and you’ll get Italian tv,” said another.

“Yeah, and the Russians are just a bit to the right of it, so you need to watch out.”

“They’re all playing sports, the whole world—I should play a bit more myself,” said Hakim with a hint of desperation.

Then his head disappeared back into the living room.

“My father-in-law fell off the roof once, trying to rescue a cat,” said a man who had just joined the others. “The cat is fine.”

“Want me to come up and hold the compass?” said a younger man.

“Go on, Khalil, give him a hand,” said an older man, presumably his father. “Russian tv is a disaster—have you ever watched the news in Russian? It’s all Yeltsin and tanks and an accent like crushed metal!” He popped another pistachio in his mouth, then shouted up, half-joking: “Should I get out the barbecue? Looks like you might be up there a while yet.” The men around me laughed. My father didn’t laugh. He paused for a moment and smiled the mischievous smile that always played around his lips when he felt a plan coming on:

“Yes, my friend, go and get the barbecue. When I’m finished here, we’ll have a party.” Then he looked down to me: “Samir, habibi, go and tell your mother to make some salad. The neighbours are coming to dinner.”

This was typical of him, the spontaneous ability to recognise a situation that ought to be savoured. If there was any opportunity to turn an ordinary moment into a special one he didn’t need to be asked twice. My father was always cloaked in an air of assurance. His infectious cheer enveloped everyone near him, like a cloud of perfume. You could see it in his eyes (which were usually dark brown but occasionally tinged with green) when he was brewing mischief. It made him look like a picaresque rogue. He always had an easy smile on his face. If the laws of nature dictated that a plus and a minus make a minus, he simply deleted the minus so that only the plus remained. Such rules did not apply to him. Except for the last few weeks we spent together, I always knew him to be a cheerful soul, tipping along with the good news in life while the bad news never found its way into his ears, as if a special happiness filter blocked it from entering his thoughts…

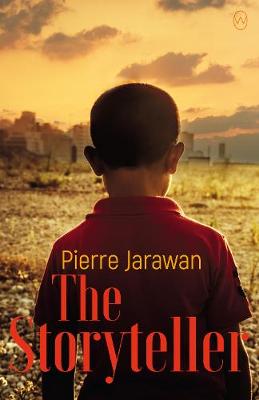

About the author –

Pierre Jarawan was born in 1985 to a Lebanese father and a German mother and moved to Germany with his family at the age of three. Inspired by his father’s imaginative bedtime stories, he started writing at the age of thirteen. He has won international prizes as a slam poet, and in2016 was named Literature Star of the Year by the daily newspaper Abendzeitung. Jarawan received a literary scholarship from the City of Munich (the Bayerischer Kunstförderpreis) for The Storyteller, which went on to become a bestseller and booksellers’ favorite in Germany and the Netherlands.

You can purchase The Storyteller (World Edition) Here.

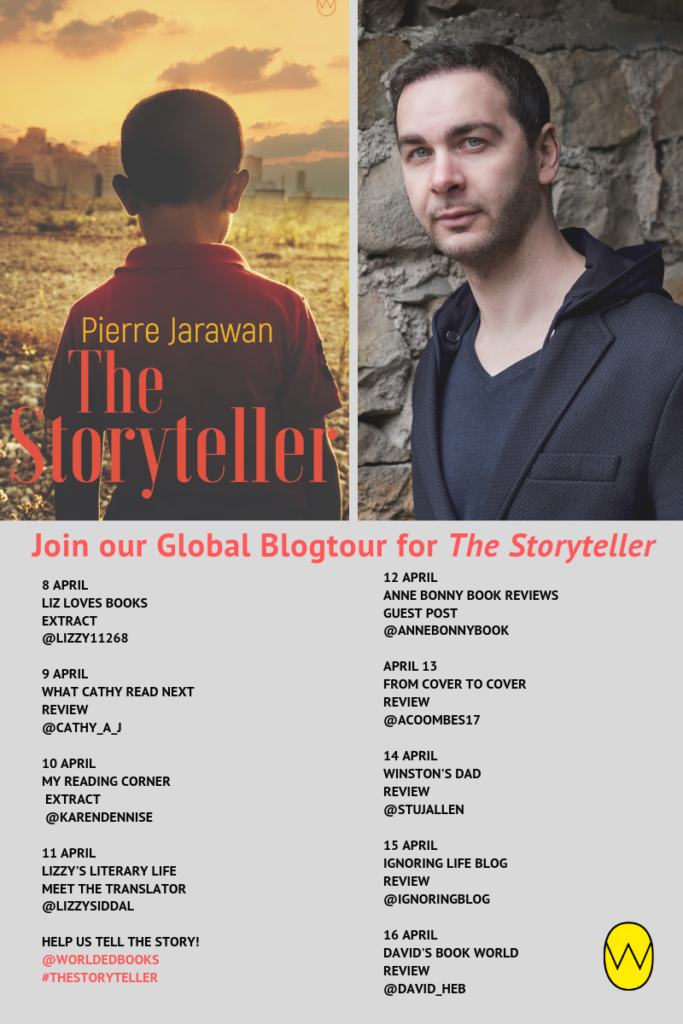

Follow the tour

Happy Reading!